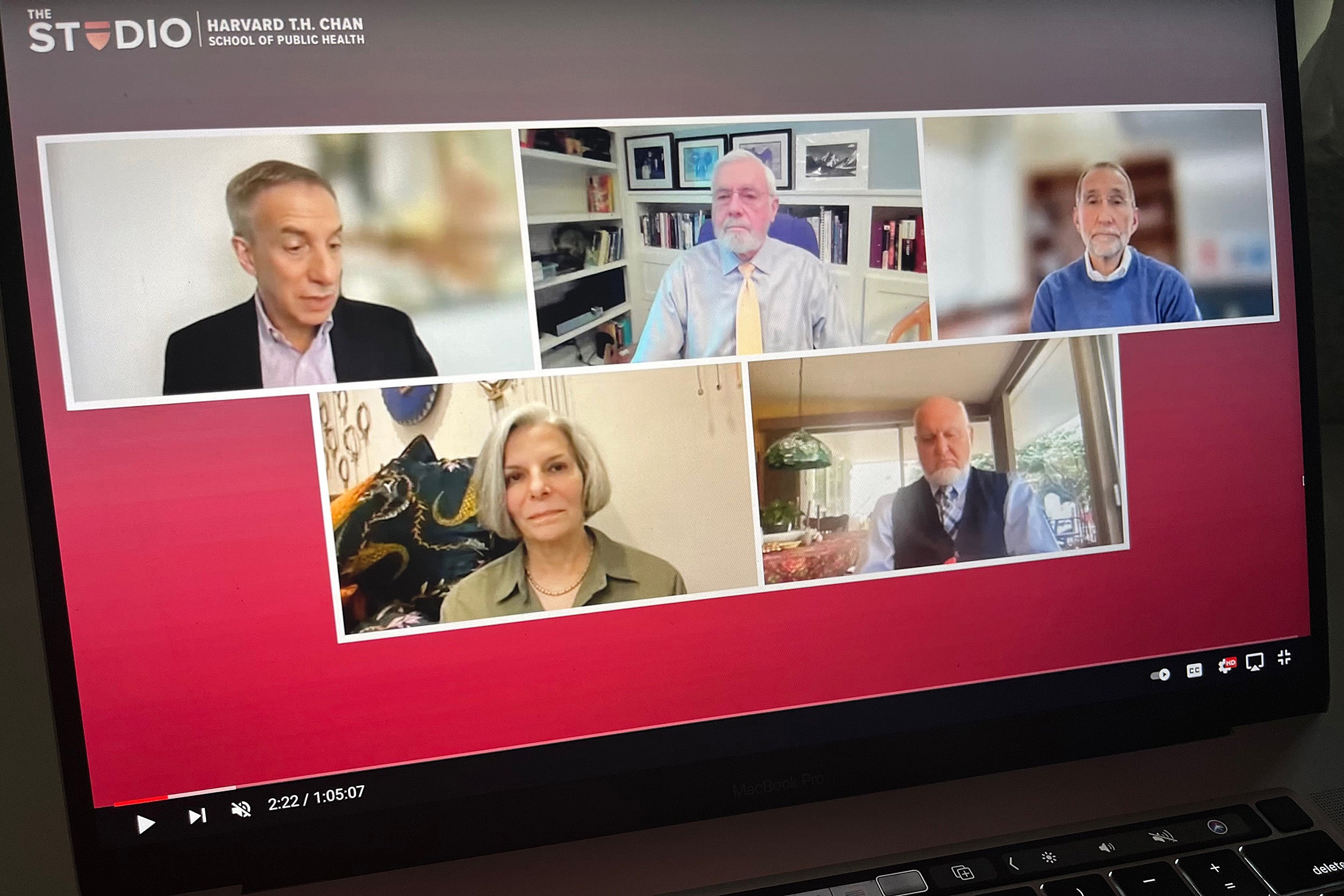

Rick Berke (clockwise from upper left) moderated a conversation among former CDC directors Bill Foege, Bill Roper, Robert Redfield, and Julie Gerberding. Additionally, Tom Frieden contributed via pre-recording video messages.

Photo by Lian Parsons

Health

What’s next for the CDC?

Former directors discuss future of the agency

On Monday, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Rochelle Walensky, announced that the agency will undergo a monthlong review to evaluate potential reforms. A day later, the Harvard T. H. Chan School for Public Health convened five former leaders of the CDC to examine challenges facing the agency and provide insight on what’s to come.

After agreeing that the review is a positive step, the panelists traded ideas on priorities and solutions. One major issue is funding. Support for the agency has not been equal to the task, said Bill Foege, director from 1977 to 1983. “The resources are always so inadequate except when we have an emergency,” he said. “You think it’s going to change, but we’re always beggars.”

Julie Gerberding, director from 2002 to 2009, added that there is very little discretionary funding at the CDC; most of its money comes from line-item budgeting, which limits potential expansion.

“Emergency funds are one-time dollars,” she said. “Those monies go away as soon as the crisis is over. We don’t make sustained investments in health equity. We’re talking about public health as a cost, but we also have to think about it as an investment in health, health protection, and cost savings somewhere else in the budget.”

Tom Frieden, director from 2009 to 2017, delivered a similar message. “We have to approach our nation’s health defense with the same urgency as our military defense. We spend 300 to 500 times less on our health defense than our military defense, and yet no war in our history has killed as many people as COVID-19 has. We need sufficient funding to break the cycle of panic and neglect.”

Political controversies surrounding public health measures have affected the CDC’s messaging, the panelists noted. A restructuring could improve the relationship between the agency and leaders in the White House and Congress, though determining the nature of such changes would likely be more complicated.

Bill Roper, director from 1990 to 1993, suggested that leadership of the agency should be a term appointment confirmed by the Senate. “The Senate confirmation process is a measure of credibility put to the position,” he said. “Other counterpart agencies are all Senate-confirmed; this one should be as well.”

Gerberding and Friedman were less enthusiastic about the idea, citing the potential for politicization. Whatever the answer, ensuring that the CDC serves the mission of public health — that it remains a scientific agency, not a political one — is the ultimate goal, said Roper.

“People say, ‘We need to get the politics out of public health,’” he said. “That is never going to happen and I think that is frankly a naive notion. We need the best of science to guide decisions made by political leaders to implement effective public health programs. The issue that we face is not a scientific question; it’s our dysfunctional political system. That can’t be solved by even the wisest people that Dr. Walensky invites in.”

Rebuilding trust between the agency and the public should be a top priority, said panelists. Investing in public health goals at the state and local level could, starting with modernizing and centralizing data systems used at the agency and at health organizations across the country.

Robert Redfield, director from 2018 to 2021, recalled a briefing on the opioid crisis at which he was told that the most recent data available was three years old.

“Data modernization is a critical tool for the CDC,” he said. “We need real-time data to execute a public health response and enhance [the CDC’s] ability to be a public health response agency. We need data that comes in at a time that is actionable.”

Foege added that improving relationships among the CDC and state, local, and tribal health authorities could also help bridge the gap.

“The CDC has never had national authority over what states do in public health,” he said. “In the past, if there was an outbreak investigation, the CDC had to be asked to do that investigation, they couldn’t just go out and do it. Now, that trust has been lost and it’s trust that holds a coalition together.”

Building a cohesive, collaborative public health community not only benefits the CDC, but strengthens global health more broadly, he added.

“Anyone working on public health anywhere is working on global health,” said Foege. “We have to see ourselves as global health equity being our objective, no matter where we’re located.”